Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Heat pumps are an excellent way to lower heating and cooling costs. Standard residential units transfer heat from the air outside to the interior of buildings — or vice versa — far more efficiently than air conditioners and furnaces that rely on fossil fuels. The result is lower heating and cooling bills — and, oh, by the way, not burning heating oil, propane, or methane means fewer climate heating pollutants, in case anyone still cares about that.

But air source heat pumps have one significant limitation. They are optimized for a certain range of air temperatures. Today’s cold climate heat pumps can provide heat when the temperature outside is well below freezing, but they struggle to provide efficient cooling when the summer sun is blazing. Heat pumps that cool effectively in summer struggle to provide heat when the mercury plummets.

There is a solution. Groundwater stays at nearly the same temperature year round, varying by only a few degrees from one season to the next. That allows a ground source heat pump to work effectively whatever the temperature is outside. The result is lower heating and cooling bills every month of the year.

The ATES Study

In a study conducted in 2024 by researchers at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Imperial College London, the data from more than 3000 aquifer thermal energy storage systems worldwide found that aquifer thermal energy storage can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 74 percent compared to conventional heating and cooling methods. “This is the LED version of heating and cooling,” Yu-Feng Lin, director of the Illinois Water Resources Center, told The Guardian recently.

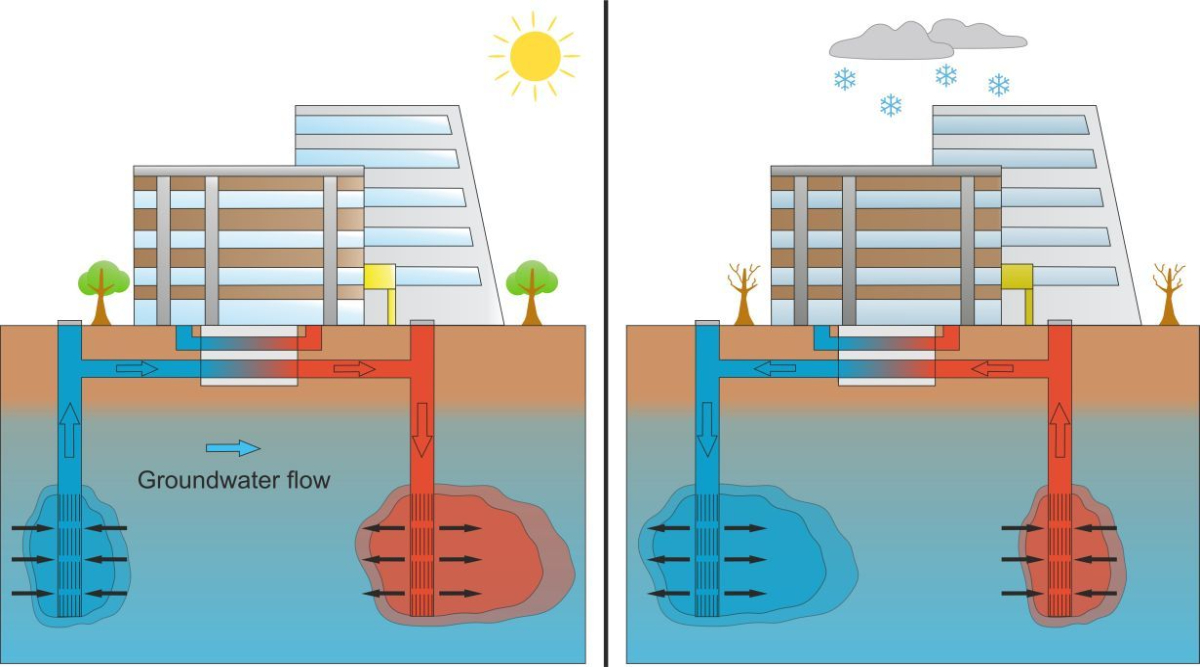

In the introduction, the researchers explain that “Aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES) is an open loop and most often shallow geothermal system that uses groundwater for seasonal storage of thermal energy. ATES systems exploit the wide availability and high heat capacity of groundwater to supply heating and/or cooling previously stored in the subsurface to mitigate temporal mismatches between energy demand and availability.

“ATES systems supplying both heat and cold are commonly used in large building complexes, such as offices, airports, universities or hospitals. This kind of ATES typically stores waste heat and cold from the cooling and heating process itself and therefore benefits from balanced heating and cooling demands of the connected buildings, which ensures sustainable system operation.”

The research shows that the return on investment — the time it takes for the savings from the systems to equal the cost of building them — can be as little as 2 years, with 10 years being a worst case scenario. Ground source heat pumps typically have a life expectancy of 15 to 20 years, while the infrastructure needed to access water in aquifers can last 80 years or more. In other words, once installed, the economic benefits continue to accrue for generations.

“Think about how much energy you are saving there,” said Lin, who is a principal investigator for an international consortium led by the US Geological Survey that develops standards and best practices for thermal energy storage. “A lot of people think about geothermal as just hot lava [and] hot steam that pushes a turbine to generate electricity. That’s not all of geothermal.”

Aquifer Energy In St. Paul

In The Heights, a mixed-use development in the Greater East Side area of St. Paul, Minnesota, Ever-Green Energy is overseeing the development of an aquifer thermal energy system that will tap thermal energy from an aquifer 300 to 500 feet below ground across the northern half of the 110 acre development. The water from the aquifer will be supplied to high efficiency electric heat pumps powered in part by solar panels. The system will provide low-cost heating and cooling with few greenhouse gas emissions for 850 homes and several light industrial buildings.

Cheniqua Johnson, a St. Paul city council member who represents Ward 7, an adjacent neighborhood on the city’s east side, told The Guardian the projected cost savings for residents of The Heights could be significant. “It is the difference between paying a $200 to $300 per month bill and less than $100,” she said. Johnson added that many people in her community have had their gas or electricity service shut off by utility companies because they were unable to pay their bills. We are not talking about McMansions here.

Policy Support In The Netherlands

The researchers emphasize that just as with other technologies such as wind and solar power, international adoption of ATES requires appropriate energy policies. Today, most of them are located in the Netherlands, which has adopted a sophisticated ATES legislative and regulatory framework. After 2000, the systems required permits governed mainly by the Dutch Water Act. Ten years later, they became so popular that a revised legislative and regulatory framework for ATES was adopted.

Today the Geo Energy Systems Amendment features a simplified 8-week permit process, company certifications to ensure high system quality, and standardized system monitoring requirements. In addition to ensuring efficient system operation, these regulations aim to protect the subsurface environment by limiting temperature changes to the water in the aquifers.

As the number of systems increased, the government also addressed increasing scarcity of subsurface space in urban areas and potentially detrimental thermal interference between systems. An interactive online map by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy allows municipalities to mark designated areas for geothermal use to aid in ATES planning.

A Comprehensive Policy Approach

To address the lack of information about ATES-specific policies in many countries, the study presents an international comparison of market barriers, policies, and regulations for ATES. It also highlights best practices for policy approaches, explores success factors and challenges from an increase in the number of systems installed, and identifies areas where appropriate policies are missing.

Those insights are a resource for creating a comprehensive ATES policy approach that addresses legislative, regulatory, and socio-economic barriers to wider international deployment of aquifer thermal energy systems in more countries. Some policy support is in place in the US, which has kept investment tax credits intact for geothermal technology while eradicating them for renewable energy.

Aquifer thermal systems are not suitable in all places. They involve drilling holes to access the water in aquifers, and the cost of the systems is inversely proportional to the depth of the wells. The deeper they are, the higher the cost.

ATES systems also have an additional dimension. They can store excess heat in the summer to make heating more efficient in the winter. Conversely, low temperatures in the winter can be captured to make cooling more efficient in summer. It’s like a two-fer — you get two systems for the price of one. Where local conditions allow, aquifer thermal energy systems make perfect sense. With luck, the new system near St. Paul will be a huge success and the good news will spread to other communities in the US. Saving money appeals to people of all political persuasions.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy