Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

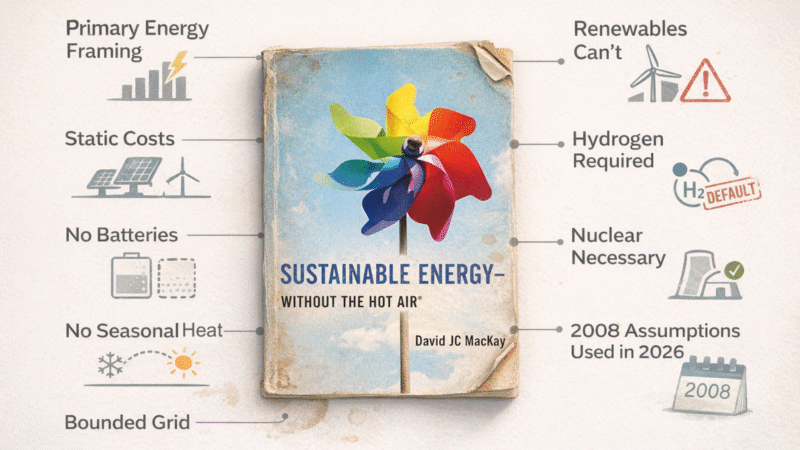

I was scrolling through energy posts on LinkedIn recently and came across yet another argument for nuclear power that leaned heavily on David MacKay’s 2008 book Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air. It was presented as a decisive reference, as if the book still represented the state of the art in 2026 rather than a snapshot of thinking from the late 2000s. That moment is what prompted this examination, not because the book lacked merit, but because it continues to be cited in ways that no longer match the reality of energy systems that have since emerged. Ideas matter, and when they persist long past the conditions that made them reasonable, they can slow progress rather than sharpen it.

MacKay’s book mattered when it appeared. It cut through a great deal of hand-waving in energy debates by insisting on numbers, scale, and physical constraints. At a time when public discussion was dominated by vague claims about efficiency and green solutions, his insistence on converting everything to comparable units and stacking supply against demand was refreshing. He forced readers to confront the fact that modern energy consumption is large, measured in tens of thousands of kWh per person per year in industrial economies, and that replacing fossil fuels would require infrastructure at similar scale. That contribution was valuable, and it explains why the book gained such traction among engineers and policymakers.

The central problem is not that MacKay was careless or ignorant. It is that his foundational framing choice anchored the analysis in primary energy, and that choice shaped the conclusions that most readers took away from the book. Primary energy accounting treats fossil fuels according to their heat content, even though most of that heat is wasted in engines, boilers, and power plants. When electrification enters the picture, this framing exaggerates the size of the problem, because electric systems deliver far more useful work per unit of energy input. MacKay did discuss efficiency gains from electric vehicles and heat pumps, but by starting from primary energy, the narrative implicitly fixed fossil era inefficiencies as the baseline. Electrification appeared as a modifier rather than as a system level transformation that collapses demand. To be clear, MacKay did not suffer from the primary energy fallacy personally, but the way he introduced and framed the discussion made it very easy for readers subject to it to hold onto their fallacy.

This framing fed directly into how solar and wind were treated. MacKay was broadly correct on the physics. Solar and wind are diffuse sources and require large collection areas. In the late 2000s, solar photovoltaics cost roughly $4 to $6 per watt installed and delivered low capacity factors in northern Europe. Wind was cheaper but still struggled to compete without policy support. MacKay concluded that both could contribute, but that they were unlikely to dominate without very large land and sea use. What he did not account for was the speed and persistence of cost declines driven by manufacturing scale and the scaling up of wind turbines. By the early 2020s, utility scale solar costs had fallen below $1 per watt in many markets, with levelized costs under $30 per MWh. Offshore wind in the North Sea reached capacity factors above 45% and costs that undercut new fossil generation. Once costs fell by 70% to 90%, feasibility shifted from physics to planning. Land use became a question of siting and consent, not of whether the system could work at all.

The largest blind spot in the book was batteries. Storage was framed as heavy, expensive, and structurally limiting. Variability in wind and solar was presented as a problem that required either massive overbuild or firm low carbon generation. At the time, grid scale batteries were rare and costly. Since then, lithium ion battery costs have fallen by about 85%, driven largely by electric vehicle supply chains. By 2025, four hour battery systems were being deployed at scale to provide peak capacity, frequency control, and short term balancing. In many grids, batteries are displacing gas peakers directly, reducing the need for firm generation capacity. This change undermines the traditional baseload argument. Once storage exists at scale, what matters is flexibility and response time, not continuous output. That shift was not anticipated in the book, and it matters because it removes one of the main structural supports for nuclear necessity.

MacKay’s treatment of heat pumps has aged better. He understood that electrifying heat with heat pumps changes energy demand fundamentally. A modern heat pump delivering a seasonal coefficient of performance of 3 converts 1 kWh of electricity into 3 kWh of heat. In countries where space and water heating account for 30% to 40% of final energy use, this alone cuts demand dramatically. Where the analysis falls short is in how seasonal mismatch was handled. Heating demand peaks in winter, while solar output peaks in summer. MacKay acknowledged this challenge and mentioned long term thermal storage in passing, including examples from the Netherlands where summer heat was stored in aquifers for winter use. What he did not do was elevate seasonal thermal storage to the status of a core system lever.

This matters because aquifer thermal energy storage and related systems were not speculative in the 2000s. Hundreds of systems were already operating in northern Europe, particularly for large buildings and district heating. These systems store heat and coolth at useful temperatures, reducing peak electricity demand in winter and improving heat pump performance. They are geology dependent and not universal, but where they are viable, they reduce the need for seasonal energy carriers. By underweighting this option, the seasonal problem appeared harder than it actually was, nudging the analysis toward hydrogen or synthetic fuels as solutions for winter balancing.

The same pattern appears in the treatment of networks. MacKay largely bounded his analysis at the UK national level. Interconnection was discussed, but it was framed as helpful rather than foundational. High voltage direct current links change system behavior in non linear ways. Wind output in the North Sea, solar output in southern Europe, and hydro storage in Scandinavia are not perfectly correlated. Trading electricity across regions smooths variability and reduces total capacity requirements. By treating continental optimization as optional, the analysis overstated the need for domestic firm generation and understated how much variability can be managed through geography.

Hydrogen enters the picture at this point as a plausible energy carrier. MacKay was clear that hydrogen pathways are inefficient, with round trip losses exceeding 60% when electricity is converted to hydrogen and back again. Yet inefficiency was treated as a cost to be managed rather than as a reason to disqualify hydrogen for most energy uses. The critical distinction between hydrogen as an industrial feedstock and hydrogen as an energy carrier was not drawn sharply. That distinction is now central. Using hydrogen as an industrial feedstock for key chemical engineering processes is unavoidable. Using it to move energy around an electrified system is optional and inferior to direct electrification.

The consequences of this framing are visible in policy tools developed under MacKay’s influence, including the UK carbon calculator. The tool makes it impossible to exclude hydrogen for energy, as I discovered when assessing it three years ago. Even when transport and heating can be electrified directly and there are multiple storage options, hydrogen remains embedded. It is possible to reduce its role in energy, but not create a scenario without it as an energy carrier. Modeling assumptions hardened into policy constraints, and those constraints justified investments in hydrogen infrastructure that now struggle to find economic roles. This is not about intent. It is about how early modeling choices shape later decisions.

When these elements are combined, nuclear power emerges as necessary within the framework. Nuclear benefits from high power density framing, static cost assumptions for wind and solar, and simplified treatment of institutional constraints. Renewables are evaluated under conservative economics, limited storage, and bounded geography. Hydrogen fills the gaps that remain. The conclusion that nuclear is required follows logically from those premises. The issue is that the premises turned out to be wrong in the places that mattered most.

It is important to note that alternative modeling existed at the same time. Mark Z. Jacobson and others were already publishing work that explored high renewables, electrification first systems without nuclear. Those models were contested, and some assumptions were optimistic. They were not flawless. But on the central questions of feasibility, cost direction, and system structure, they were much closer to what actually happened. That difference did not arise from access to secret data. It arose from different choices about system boundaries, learning curves, and what technologies were allowed to scale.

Today, Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air is often cited to argue that renewables cannot deliver, that hydrogen is unavoidable, and that nuclear must be central. This use strips the book of context and freezes it in time. It also ignores the very efficiency arguments MacKay himself made, and at least in the case of renewables, MacKay’s own strong support for them, even if in a much smaller role than they will play. The problem is that the book’s specific misses make it easy to misuse. It reads as sober and numerical, and it was written by a respected and now departed physicist. That gives it rhetorical weight long after its assumptions expired.

Being fair requires acknowledging what could not reasonably have been predicted. No one in 2008 knew exactly how fast solar, wind and battery costs would fall or how quickly offshore wind would scale. Being honest requires acknowledging that others, working in the same period, reached conclusions that history validated more strongly. Respect for MacKay does not require pretending that his analysis and book aged well.

What remains valuable in the book is the discipline of arithmetic and the insistence on scale. What should be retired are the primary energy anchoring, the acceptance of hydrogen as an energy carrier, the lack of economic drivers for wind and solar, and the framing that makes nuclear appear structurally necessary. In 2026, anyone citing the book as anything other than a historical artifact is hard to take seriously in energy discussions. The world it described no longer exists, and clinging to it delays the work of building the electrified, renewable dominated system that has already proven itself in practice.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy