Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

CATL’s batteries and energy management systems are already operating in roughly 900 ships and vessels, a figure that on its own should reframe how maritime decarbonization is discussed. Shipping is conservative for structural reasons tied to safety, long asset lifetimes, and unforgiving certification regimes, so deployment at this scale signals that electrification is no longer a pilot exercise but operating infrastructure. While much of the public debate remains focused on alternative fuels that are expensive, supply constrained, or operationally complex, electrification has been advancing quietly in the parts of maritime transport where it actually works today.

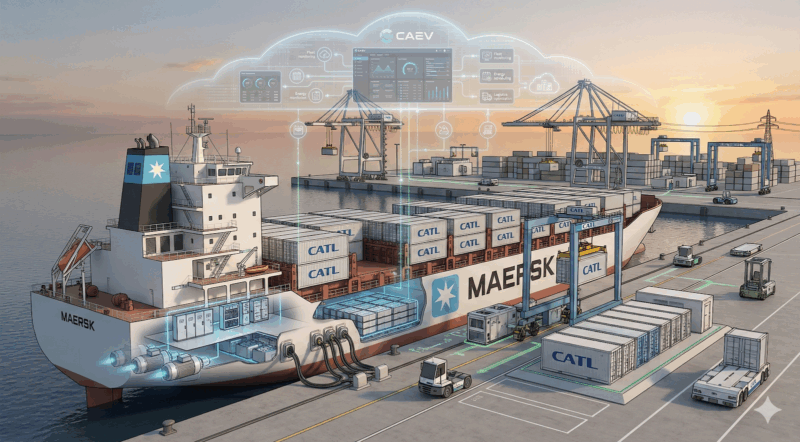

That reality became clearer when CATL—China’s and the world’s largest battery company—, through its marine subsidiary Contemporary Amperex Electric Vessel (CAEV), unveiled its Ship-Shore-Cloud electric vessel solution at Marintec China 2025 in early December. The announcement was not framed around a single battery product or a demonstration vessel, but around integration across the full operating stack. Onboard, CATL combines batteries, power electronics, propulsion integration, and control systems into certified packages designed for multi-decade service. Onshore, it pairs those systems with charging and battery swapping infrastructure, including a separation of ship and battery model that lowers upfront capital requirements and reallocates risk. At the cloud layer, fleet operators gain continuous monitoring, scheduling, maintenance planning, and optimization across entire fleets. The underlying premise is straightforward. Fragmented supplier models create coordination failures, unclear accountability, and avoidable downtime over a 30 year asset life, while integrated systems reduce operational risk and lifecycle cost.

The significance of that approach becomes clearer when examined against the vessels already operating at scale. CATL’s systems power Changjiangsanxia 1, a roughly 100 meter all electric inland passenger ship carrying more than 1,000 passengers daily on the Yangtze River in the Three Gorges region. Along China’s coast, the Yujian 77 electric passenger vessel operates on short sea routes in places such as Xiamen Bay, meeting China Classification Society requirements for corrosion resistance, redundancy, and marine safety in saltwater conditions that are far harsher than inland rivers. In ports, hybrid tugboats such as Qinggang Tug 1 are handling high transient power demands during ship assist operations, demonstrating that batteries can absorb peak loads and cut diesel use and local air pollution in dense harbor environments.

On the cargo side, the Jining 6006 electric vessel is moving freight along sections of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal using containerized battery swapping, where batteries are exchanged in minutes rather than hours, showing that downtime rather than energy density is often the real constraint for commercial operations. Two sister 700 TEU battery-electric container ships, N997 and N998, built for COSCO Shipping Development and operating on the Yangtze River with swappable containerized batteries, do not use CATL systems but are still indicative of how quickly large-scale inland container shipping is moving toward electrification in China. These deployments are not fringe experiments. They sit squarely in inland waterways, coastal passenger routes, ports, and canals, precisely where electrification is most practical and where emissions have the greatest impact on nearby communities.

The strategic context sharpened further in 2025 when CATL and A.P. Moller Maersk formalized a series of agreements spanning ports, terminals, and logistics. Through Maersk’s terminal arm APM Terminals, CATL batteries are being deployed into electrified container handling equipment and terminal vehicles, a segment where electrification is already economically compelling due to predictable duty cycles, centralized charging, and clear total cost advantages. I’ve spent considerable time talking with Sahar Rashidbeigi about APM Terminal’s electrification efforts under her four years leading the effort, now over as she has taken a new role as VP Decarbonization for the Royal Carribean Group cruise line company.

Beyond terminals, the broader CATL–Maersk strategic partnership positions CATL as a preferred battery and energy technology partner across logistics and supply chains. For Maersk, the value lies in decarbonizing assets without compromising reliability or competitiveness. For CATL, the value lies in embedding its technology into a global operational platform where scale, standards, and learning effects reinforce each other. Clearly Maersk is seeing the strong advantages of electrification of as much of the supply chain it operates as possible.

This trajectory aligns closely with the multi decade port electrification strategy I have laid out in my earlier work. In that analysis, I argued that ports function most effectively as energy hubs rather than fuel depots, because electricity scales incrementally, integrates cleanly with grids, and improves reliability instead of introducing new handling risks. The sequencing matters. Ground equipment electrifies first because the technology is mature and the economics are already favorable. Harbor craft follow because their duty cycles are short, predictable, and power intensive. Shore power then becomes routine for vessels at berth, eliminating auxiliary engine use in precisely the places where air pollution is most visible and politically sensitive. Grid capacity and onshore and offshore renewables expand alongside these changes as demand materializes, rather than being built speculatively in advance. Only after these steps are well underway does it make sense to address the hardest segments of deep sea shipping. This is not an abstract preference. It is an operational strategy that builds infrastructure, workforce capability, regulatory familiarity, and confidence while delivering emissions and cost reductions at each stage.

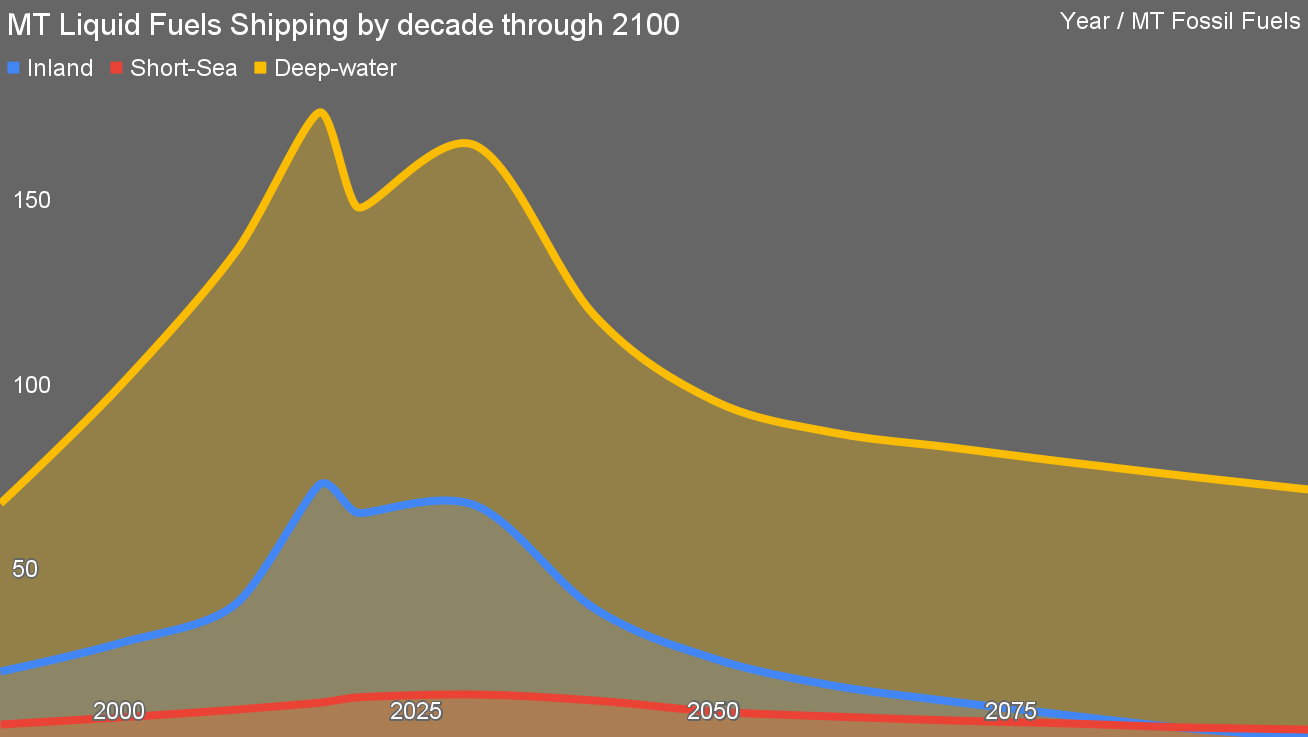

In my earlier scenario of maritime shipping decarbonization, I projected that most of the visible progress over the next two decades would come from inland shipping, ports, and short sea routes rather than from transoceanic vessels. Inland waterways and coastal services have constrained ranges, centralized charging opportunities, and fixed schedules, all of which favor battery electric propulsion. Ports, meanwhile, are stationary energy consumers that can anchor grid upgrades, renewable integration, and storage, creating spillover benefits for surrounding industries. As these systems scale, batteries become cheaper, operational data accumulates, and standards harden, further lowering barriers to adoption. None of this requires breakthroughs. It requires deployment.

My view on deep sea shipping has always been more conditional. Long haul ocean vessels face genuine energy density constraints that batteries alone cannot solve today, and pretending otherwise does not help the sector. That does not mean decarbonization stalls. It means the pathway is slower and more selective. Operational changes such as speed reductions deliver immediate emissions cuts. Hybridization allows batteries to cover port entry, maneuvering, and auxiliary loads, shrinking fuel demand even when liquid fuels remain necessary. Sustainable biofuels have a role in that context, not as a universal solution but as a limited substitute where electrification cannot yet reach. As I noted after working with TenneT in The Netherlands in the summer of 2025 on their 2050 full country energy decarbonization scenario, core discussions of the economic merit order of aviation versus shipping demand for the feedstocks most suitable for making aviation fuels led to my assumption that biomethanol would be a dominant shipping fuel after all. Subsequent assessment of US corn ethanol futures and an ongoing research effort on pathways to aviation fuels from waste biomass and agricultural feedstocks—expect a series including updates to my aviation scenario soon—lead me to believe that ethanol will also be a likely shipping fuel, especially for ships bunkering in US and Brazilian ports.

Over time, as ports become fully electrified energy hubs and short sea routes normalize electric propulsion, the pressure on deep sea shipping eases because a growing share of maritime activity has already decarbonized and global shipping of fossil fuels—40% of total shipping tonnage today—and raw iron ore—another 15%—will be in structural decline. The mistake is to treat the hardest problem as the first one to solve. The evidence from ports and inland shipping shows that working outward from what is feasible now delivers faster, more durable progress.

When viewed through that lens, CATL’s Ship-Shore-Cloud strategy looks less like a product announcement and more like an operating system for maritime electrification. Integrated onboard systems depend on standardized shore charging, grid upgrades and energy management. Fleet-level monitoring reduces downtime and clarifies accountability across decades of operation, while battery swapping and service models smooth adoption by shifting capital and performance risk. Many battery suppliers sell components into this ecosystem. CATL is positioning itself as a platform provider spanning assets, infrastructure, and operational data.

China’s national policy environment reinforces that positioning. Inland shipping and ports sit squarely within China’s dual carbon objectives of peaking emissions before 2030 and reaching carbon neutrality by 2060, with national and provincial policies emphasizing low carbon ports, electrification of port equipment, expansion of shore power, and modernization of inland waterways. Rivers such as the Yangtze carry immense freight volumes through dense population centers, with predictable routes and centralized nodes that favor electrification earlier than almost anywhere else. Policy support, industrial capacity, and domestic scale combine to create learning curves that compound quickly, allowing standards proven at home to become export standards as deployments accumulate.

CATL is not operating in isolation, even if it is the most visible player at scale. Other Chinese battery manufacturers are already active in or moving decisively toward the maritime space, drawing on the same industrial strengths that reshaped automotive electrification. BYD, through its energy storage and marine subsidiaries, has supplied batteries and complete electric propulsion systems for ferries and workboats, particularly in coastal and inland applications. EVE Energy has obtained marine certifications and is supplying lithium iron phosphate cells and packs into electric and hybrid vessels, often through partnerships with ship system integrators. CALB and Gotion High-Tech are also present, supplying cells and modules used in marine energy storage systems that meet classification society requirements. In parallel, firms such as Lishen, Sunwoda, Great Power, and REPT are positioning their products for maritime use, leveraging scale from automotive and stationary storage markets. What distinguishes this group collectively is not just manufacturing capacity, but proximity to Chinese shipyards and system integrators, which allows batteries, power electronics, and energy management systems to be designed into vessels from the outset. The result is a deep and growing ecosystem of Chinese battery suppliers capable of supporting electrified shipping, even as CATL remains the clear leader in integration, deployment count, and strategic reach.

This stands in sharp contrast to the role the United States has played, where federal policy has actively attacked or undermined progress rather than merely failing to lead. By scuttling decarbonization measures at the International Maritime Organization, the United States has injected uncertainty into a sector that depends on long lived assets and stable standards. That uncertainty has predictable effects. Shipowners will delay retrofits, many ports will hesitate on grid and shore power investments, and capital will wait for clearer signals, even where electric solutions are already viable.

The structural reasons for this posture are not subtle. The United States has a lagging battery manufacturing sector compared with China, no meaningful commercial shipbuilding industry at scale—South Korea, Japan, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Norway, and Finland each have larger commercial shipbuilding industries than the United States, even though taken together they have a smaller combined population and less than half the GDP of the country—, and a Jones Act regime that sharply limits domestic vessel competition and renewal. Those constraints inhibit electrification of vessels operating in US, Canadian and Mexican waters and make it difficult for American firms to compete with companies like CATL that combine battery manufacturing scale, certified marine systems, and integration across ships, ports, and operations. Instead of addressing those weaknesses, US policy has leaned toward blocking international progress, which slows global decarbonization while doing little to improve domestic competitiveness. The result is a widening gap between countries aligning policy with industrial reality and those attempting to defend legacy structures that no longer match the direction of maritime technology.

Europe occupies a middle ground in maritime electrification, with a shipbuilding industry far smaller than China’s but still robust and globally relevant, and a narrower battery manufacturing base. It has combined port electrification with real-world shipping deployments under a strong policy push, pairing shore power mandates, carbon pricing through the EU emissions trading system, and regulations such as FuelEU Maritime with large-scale demonstrations of battery-electric and hybrid vessels. Electrification of ferries is already routine in Norway, Denmark, Scotland, and the Baltic on fixed routes, while ports across the EU are upgrading grids and berth infrastructure in response to binding decarbonization targets that are steadily reshaping both port operations and short-sea shipping. It will still electrify much more slowly than China, but the Maersk-CATL agreements promise to speed this considerably.

Taken together, these dynamics support a clear conclusion. CATL, as China’s and the world’s leading battery manufacturer, is positioning itself to become the dominant global player in port and shipping electrification, combining manufacturing scale, certified marine technology, integrated service models, and anchor partnerships with operators such as Maersk. That strategy is reinforced by national Chinese policies that emphasize electrifying inland shipping and ports using technologies that are already commercially viable, rather than deferring action in favor of speculative fuel pathways. The result is not a promise about the distant future of shipping, but a concrete reshaping of how large parts of the sector are already operating.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy