Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

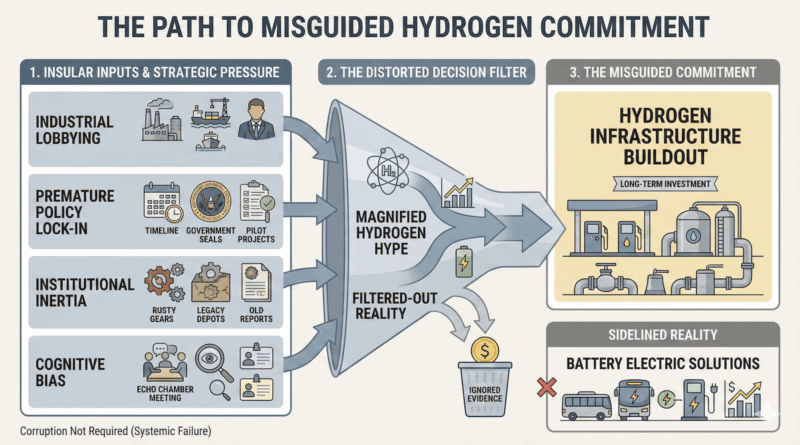

The question comes up regularly when hydrogen transportation projects fail in ways that are no longer surprising, most recently in a comment on my article that lead with the UK’s HyRoad’s dissolution. Battery electric buses work well in city after city, while hydrogen buses struggle, stall, or collapse. Observers reasonably ask whether corruption must be involved, because it seems implausible that rational decision makers would repeatedly choose the worse option. The intuition is understandable, but it turns out to be the wrong frame for most cases. What looks like corruption from the outside is usually a combination of institutional structure, delegated authority, incentive misalignment, lobbying that stays inside legal bounds, cognitive bias, and industrial policy path dependence.

To be very clear, most people involved most of the time are working hard to make the best decision for the citizens that they serve and the transit agency itself. Their intentions are almost always good, but a variety of factors lead them to bad decisions. The number of actual bad actors in the system is low, although they are present. But even there, the individuals engaged from those bad actors usually believe the narrative that they lobby for, with various combinations of cognitive biases driving their incorrect positions. The number of ill-intentioned people engaged in transit decisions is very low, and they are rarely influential.

So what is going on?

Public transit agencies are not structured to be strategic technology evaluators. They are structured to run buses on time, keep operators safe, manage labor agreements, and stretch constrained budgets. That makes them operationally strong and strategically weak. The last major technological transition most transit agencies experienced was the move from trolley buses to diesel buses in the middle of the 20th century. Since then, propulsion systems changed little for decades. As a result, no institutional muscle developed around comparative technoeconomic assessment of propulsion systems. Procurement became about choosing between nearly identical diesel options from different vendors. When decarbonization arrived, many agencies simply did not have the internal capability to evaluate whole system costs, infrastructure implications, reliability risks, or learning curve trajectories across technologies.

This gap is visible across jurisdictions. In my writing on battery electric bus deployments in cities such as Shenzhen, Oslo, and multiple European capitals, the success was not driven by heroic internal analysis at individual transit agencies. It was driven by external frameworks that made the choice obvious and low risk. Where those frameworks did not exist, agencies defaulted to deference rather than analysis. If one staff member did understand the differences between battery electric and hydrogen systems, that understanding often failed to translate into institutional action. Technical insight without organizational authority tends to dissipate rather than accumulate.

That deference flows upward. Transit agencies expect national or regional bodies to do the heavy analytical lifting. In many regions where hydrogen fleets emerged, those upstream bodies were actively promoting hydrogen. This was not usually malicious. In the early 2010s, battery electric buses were improving rapidly but had not yet demonstrated clear dominance in cold climates, long duty cycles, or high utilization routes. At the same time, governments were under pressure to decarbonize transport and saw hydrogen as a way to align climate goals with domestic industrial policy, particularly in regions with strong natural gas, chemical, or fuel cell sectors.

In Canada, this dynamic was visible through federal programs administered by Natural Resources Canada. Transit agencies were told hydrogen was acceptable because federal funding programs approved it. If the federal government was willing to cover up to 80% of the cost of a fleet decarbonization strategy that included hydrogen, agencies had little incentive to challenge the premise. A senior city manager told me this year that their hands were tied. If the federal program approved hydrogen and paid for it, rejecting it required political capital that transit agencies do not possess in abundance. Programs like this change slowly. Even as evidence accumulated that hydrogen buses were underperforming and expensive, the funding structures continued to validate them.

The CUTRIC case in Canada illustrates how process failures can create distorted outcomes without crossing into criminal corruption. CUTRIC positioned itself as the national transit decarbonization think tank and successfully lobbied to become the sole approved advisory body for federally funded fleet strategies. This happened not because it was uniquely competent, but because it was available, well connected, and aligned with prevailing policy narratives. Large engineering firms such as Stantec, WSP, or Deloitte did not bid in the narrow window available, leaving CUTRIC unopposed. Once sole sourced, CUTRIC became the gatekeeper for hundreds of millions of dollars in public spending.

The governance of CUTRIC compounded the problem. Its largest corporate members included natural gas utilities, a hydrogen fuel cell manufacturer, and the only bus OEM selling hydrogen buses in Canada. Those firms benefited directly if hydrogen was selected. Board members did not need to falsify data or bribe officials. They simply needed to frame hydrogen as viable, innovative, and future facing. In my past critiques of CUTRIC, I pointed out that this governance structure created obvious conflicts of interest and poor optics. It was unwise and ethically questionable. It was not bribery. No evidence has emerged of kickbacks, fraud, or personal enrichment tied to specific procurement decisions.

The federal Zero Emission Transit Fund that funded CUTRIC and previous rounds of hydrogen buses in Canada has now wrapped up, and its replacement program has materially changed the landscape that enabled some of the earlier hydrogen decisions. One of the most important shifts is that advisory work is no longer effectively sole sourced. CUTRIC is no longer the only advisory body permitted to receive federal funding for fleet decarbonization strategies, and must now compete with other firms and consortia.

At the same time, CUTRIC’s Board composition has changed, with the departure of members whose commercial interests were directly aligned with hydrogen outcomes, including firms that only benefited financially if hydrogen buses were selected. Whether this governance cleanup was a cause or an effect of CUTRIC’s reduced influence is not entirely clear. It is possible that board members stepped away once CUTRIC was no longer a privileged gatekeeper for federal funding. It is also possible that the Board itself recognized the governance problem and acted to correct it. Either way, the combination of program redesign and board changes has removed a structural distortion that previously amplified hydrogen recommendations without requiring any corrupt behavior to do so.

This doesn’t, in my opinion, mean that CUTRIC is competent to advise transit agencies. It clearly does not have the ability to perform analyses of fleet decarbonization, with its major Brampton report for example seeing Deloitte subcontracted in. It doesn’t show any strategic insights about transformation in general or transit fleets in particular. Its models are not aligned with empirical reality on hydrogen. As actually competent organizations are now able to bid on fleet decarbonization strategies, the overall outcomes should be somewhat better, although Deloitte’s involvement with the scandalously bad Brampton report doesn’t guarantee anything. That said, I know actually competent and knowledgeable people at Stantec and WSP, as two obvious examples, who can provide good, unbiased guidance.

Even there, all major consultancies dug into hydrogen for energy and transportation plays because getting paid work for their staff is their business model, and there was money in hydrogen. That means that there are entire teams who are deep in the hydrogen bubble still, even as it collapses around them. They are still chasing the smaller and smaller number of available deals, and will push themselves into Canada’s transit decisions if they can. Systemically, Canada is far from out of the woods in terms of advisory services to transit.

Lobbying operates in this space as an ambient force rather than a scandalous one. Natural gas utilities appear repeatedly when tracing hydrogen decisions across Canada, as noted in the CUTRIC membership and Board, and elsewhere. Companies like Enbridge are major employers, long standing suppliers, and regulated utilities embedded in municipal operations. They sponsor conferences, provide technical briefings, and meet regularly with city councillors and senior staff. They argue that hydrogen preserves jobs, leverages existing infrastructure, and avoids disruptive electrification. These arguments are often wrong, as I have shown in multiple analyses of heat pumps, grid capacity, and lifecycle emissions. But the presence of these companies as trusted partners makes their narratives sticky.

This does not require bribery to be effective. A councillor who has worked with a gas utility for a decade, relies on it for emergency response coordination, and hears consistent messaging about reliability and affordability will give that messaging weight. When that utility says hydrogen is a solution, it sounds credible. In discussions with energy NGOs and municipal insiders, I repeatedly hear stories of utilities shaping decisions through persistence rather than payment. This is influence, not corruption in the legal sense.

Cognitive bias plays a large role, especially in regions that tried to decarbonize early. California is the clearest example. For decades, the state pushed alternative fuels well before battery electric vehicles were ready at scale. That created a hydrogen ecosystem of startups, lobbyists, academics, advocacy groups, and bureaucrats. Many of these actors built careers and identities around hydrogen. When battery electric technology overtook hydrogen, the ecosystem did not dissolve. It defended itself. Evidence that contradicted its assumptions was discounted or reframed. I have described this dynamic in my writing as self healing belief systems, where failure leads to calls for more funding rather than reassessment.

A notable example was the EU’s 2023 hydrogen status report. It was a litany of failures in all of the details. The frame of the executive summary was that more money needed to be spent on hydrogen so that it could compete with battery electrification, which was outstripping it everywhere. The empirical data presented by itself was damning of hydrogen for transportation, but when compared with the rapid advance of battery electric, the only real conclusion was that the hydrogen experiment had been run and needed to be defunded. Yet that’s not what happened or is happening.

Industrial policy reinforces these patterns. Regions develop economic strategies based on existing strengths. Oil and gas regions look for green molecules that allow continuity. Ports and heavy industry hubs see hydrogen as a way to remain relevant without electrifying everything. University programs in electrochemistry produce graduates eager to commercialize hydrogen technologies, who then lobby governments to create markets for them. British Columbia offers an example where academic advocacy, provincial policy, and startup ambition aligned around hydrogen despite weak economic fundamentals.

None of this requires corruption. It requires optimism, institutional inertia, and a preference for solutions that feel familiar. Making the wrong industrial policy bet is common. Governments do it regularly. The problem arises when those bets persist long after evidence turns against them. Legacy programs, sunk costs, and political pride make reversal difficult.

Across my publications on hydrogen transportation, from buses to trucks to trains, a consistent pattern emerges. Evidence loses to process. Procurement rules, funding eligibility, advisory monopolies, governance structures, lobbying relationships, and cognitive commitments all shape outcomes more than comparative performance data. Battery electric buses win on cost, reliability, and energy efficiency. Hydrogen buses lose on all three. Yet decisions lag because institutions move slowly and incentives are misaligned.

Calling this corruption obscures the real lessons. In most cases, actors believed they were acting responsibly within the frameworks they were given. The failures are systemic. They reflect how public sector decision making actually works under uncertainty and pressure, not how it works in economic textbooks.

The cost of these failures is real. Hydrogen buses cost more upfront, cost more to operate, and deliver less reliable service. They divert public funds from proven solutions, slow emissions reductions, and leave cities with stranded assets. They also erode public trust when promised outcomes fail to materialize. In my analyses of fleet transitions, the opportunity cost often exceeds the direct cost. Every $10 million spent on a hydrogen pilot that stalls is $10 million not spent electrifying routes that would have delivered immediate benefits.

Correction eventually comes, but it is slow. Programs expire. Advisory monopolies are dismantled. New procurement rules emphasize total cost of ownership and operational data. Younger engineers and planners arrive without legacy attachments. Battery electric dominance becomes undeniable as deployments scale. The hydrogen ecosystem for transport shrinks as funding dries up and firms pivot or fail, a trend I have tracked repeatedly.

This is not a story of villains and bribes. It is a story of institutions designed for stability struggling to adapt to rapid technological change. Understanding that distinction matters, because fixing governance, procurement, and analytical capacity does far more to prevent future failures than hunting for corruption that usually is not there.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy