Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

The Liverpool City Region decision to convert its hydrogen bus fleet to battery electric operation was presented publicly as a response to changing market conditions. For observers who have followed hydrogen transport projects for more than a few years, it read less like a surprise and more like another entry in a familiar sequence. Similar announcements have emerged from cities, regions, and operators across Europe, North America, and parts of Asia. Each time, the explanation focuses on local constraints or short term supply challenges. Each time, the broader pattern is left largely unexamined.

I’ve described that pattern as the odyssey of the hydrogen fleet. It is not a rhetorical device but a descriptive one. A hydrogen transport project begins with strong political and institutional enthusiasm, anchored in the promise of zero tailpipe emissions and compatibility with existing vehicle concepts. Public funding is secured, often justified as a pilot or early market stimulus. Vehicles are ordered, fueling infrastructure is planned, and the project is announced as a stepping stone toward scale. At this stage, expectations are high and scrutiny is limited.

The next phase is initial deployment. Vehicles arrive later than planned, infrastructure proves more complex than anticipated, and early operations are constrained. Hydrogen supply is inconsistent or costly, maintenance requires specialist support, and utilization rates remain low. These challenges are rarely framed as structural. They are treated as teething problems that will be resolved with experience, learning, or additional funding.

As time passes, the operational burden becomes clearer. Fuel costs remain high and volatile. Infrastructure downtime affects service reliability. Spare parts and trained technicians are scarce. Fleet expansion is delayed or quietly abandoned. Operators begin to limit deployment to showcase routes or special duties. Public communication shifts toward optimism about future improvements while day to day use declines.

Eventually, the project reaches a decision point. Continued operation requires renewed subsidies, higher fares, or service compromises. At the same time, battery electric alternatives are improving and becoming more available. Faced with this comparison, operators and authorities reassess. Hydrogen assets are mothballed, sold, or converted. The original rationale is rarely revisited in detail. The project is framed as a learning experience, and attention moves on.

Liverpool fits this sequence closely. The hydrogen buses were delivered, but fuel supply constraints limited regular service. After a recent review, the region chose to convert the vehicles to battery electric operation rather than persist. As a reminder, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are simply limited range battery electric vehicles with a complex and cranky bolted on hydrogen electricity generator that can be replaced with more batteries. This was not an isolated choice made in ignorance of alternatives. It was a rational response to comparative performance and cost. What is notable is not the decision itself, but how often similar decisions have been taken elsewhere under similar conditions.

In California, multiple transit agencies trialed hydrogen buses over the past two decades. Reports from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory documented high fuel costs, low availability, and maintenance challenges. Fleets did not scale beyond pilot size without sustained subsidy. Most agencies chose battery electric buses once they became viable. In Europe, Germany invested heavily in hydrogen buses and trains. Many deployments struggled with fuel logistics and reliability, leading to reduced utilization or replacement by battery electric alternatives. In the UK, hydrogen bus projects in Aberdeen, Birmingham, and now Liverpool have followed comparable arcs. Nordic countries saw hydrogen buses withdrawn after short operational lives. The Netherlands and Belgium reported similar outcomes.

Beyond buses, hydrogen trains provide another set of case studies. Germany and the UK both introduced hydrogen multiple units on non electrified lines. Initial services attracted attention, but cost comparisons with battery electric trains charged from the grid or from overhead wires favored batteries. Several operators pivoted accordingly. Hydrogen refuse trucks, port vehicles, and light commercial fleets show parallel patterns. Pilots launch, operate at limited scale, and then stall.

At this point, a reasonable question arises. Where are the counterexamples? A meaningful counterexample would be a hydrogen transport fleet that operates at scale for several years, expands without escalating subsidy, secures reliable fuel supply at declining cost, and is replicated by independent operators. Claims are sometimes made about such cases, often pointing to China or Korea. Closer examination shows that these fleets remain heavily policy supported, geographically limited, and insulated from market comparison. They do not demonstrate cost convergence or organic replication.

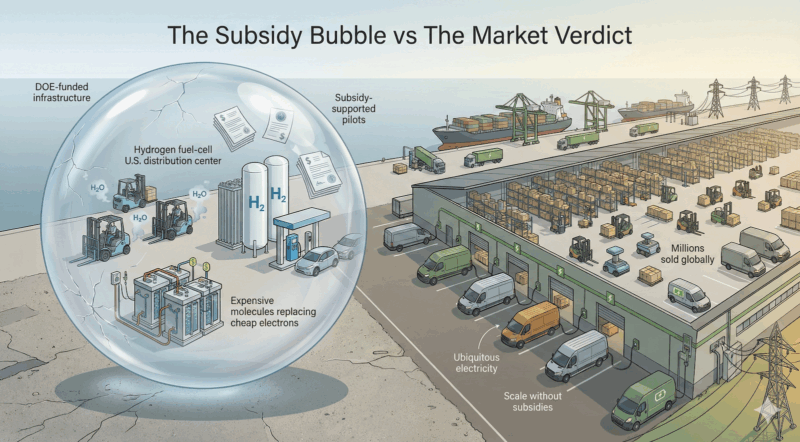

The oft-cited tens of thousands of hydrogen fuel-cell forklifts scattered across a subset of U.S. distribution centers are a triumph of subsidy choreography, not market logic. They exist largely because the U.S. Department of Energy and allied programs paid for the hydrogen fueling infrastructure, smoothed early capital costs, and kept writing checks to Plug Power and its ecosystem to keep the story going. Strip away the grants, tax credits, and bespoke refueling build-outs and the value proposition collapses fast: hydrogen forklifts trade cheap electricity for expensive molecules where they use green-ish hydrogen at all, add operational fragility, and lock warehouses into single-vendor fueling dependencies. Meanwhile, the rest of the world has voted with its wallets. Battery-electric forklifts dominate global sales by an overwhelming margin, millions per year in unit sales—not because they’re fashionable, but because they’re simpler, cheaper, more reliable, and plug into ubiquitous power. In short, hydrogen forklifts are a US federally curated side quest in a market that long ago chose batteries and moved on.

This leads to a broader epistemological question. At what point does a large collection of anecdotes and case studies become evidence? In engineering disciplines, repeated failures across independent contexts are treated as data. When the same failure modes appear in different systems, designers look for underlying causes rather than attributing each instance to circumstance. In medicine, case series precede statistical trials and guide hypotheses. When patterns saturate across settings, confidence increases even without randomized controls.

Hydrogen transport projects now exhibit pattern saturation. Across continents, vehicle types, operators, and policy regimes, the same outcomes recur. High energy losses in production and distribution translate into high operating costs. Complex fueling infrastructure introduces reliability risks. Low utilization magnifies fixed costs. The vast majority of hydrogen actually consumed is fossil fuel derived with high well to wheel emissions, often higher than the diesel vehicles they replace. These are not incidental issues. They are direct consequences of the physics and economics of hydrogen as an energy carrier.

The physical constraints are well understood. Producing hydrogen from electricity incurs large conversion losses. Compressing, liquefying, transporting, and dispensing hydrogen adds further losses and capital costs. Leakage reduces delivered energy and contributes to indirect greenhouse effects. Vehicles require fuel cells, high pressure tanks, and balance of plant components that add cost and maintenance complexity. None of these factors improve materially with scale in the way battery costs have declined.

Battery electric transport offers a useful control case. Electric buses, trucks, and trains have scaled rapidly. Their energy efficiency is high, infrastructure builds on existing grids, and learning rates have driven down costs. Operators report improving reliability and lower total cost of ownership. The technology is unremarkable in daily use, which is precisely the point. Its success does not depend on special treatment or sustained narrative support.

Given this contrast, the persistence of hydrogen transport proposals requires explanation. Institutional momentum plays a role. Once funding streams and industrial strategies are established, they generate projects. Hydrogen also appeals as a familiar fuel narrative, allowing continuity with existing vehicle concepts and supply chains. In some cases, hydrogen transport serves as a policy placeholder, signaling climate intent without confronting harder choices about electrification.

There is also a deeper structural motive at work: for the usual suspects in the energy sector, keeping molecules central to the story is the point. Molecules preserve existing business models, assets, and hierarchies. They justify pipelines, tanks, terminals, fuel contracts, and the operational cultures built around them. Hydrogen, in particular, offered a convenient first act in this odyssey: a new molecule that could be presented as revolutionary while still fitting neatly inside old mental models of fuel production, distribution, and combustion. Fleets, depots, and refueling stations looked comfortingly familiar, even as the economics quietly worsened. That initial hydrogen fleet chapter mattered less for what it delivered than for what it protected. It kept liquid and gaseous fuels in the energy conversation at a moment when electrons were beginning to displace them. As with many such transitions, the early narrative was not about technical inevitability, but about buying time for incumbents to remain relevant in a game that was already moving away from molecules altogether.

For policymakers and procurement bodies, the lesson is not that experimentation was misguided. Early trials generated information. The lesson is that information now exists in abundance. Continuing to frame each new hydrogen fleet as a fresh experiment ignores accumulated evidence. Decision processes need clearer exit criteria, stronger comparative analysis, and greater willingness to update assumptions.

Predictability is often mistaken for inevitability. In this case, predictability is information. The repeated arc of hydrogen transport projects is not a series of unfortunate surprises. It is a consistent response to underlying constraints. Treating it as such would allow public resources to be directed toward solutions that demonstrate durable performance rather than revisiting the same odyssey under new names.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy